What's the problem with purity?

Shouldn't we want pure things? Like water, bodies, nations, and soap?

Evangelical Purity Culture and Its Discontents came out earlier this year and includes an essay by yours truly, “When Purity Cannot Save Us: On Matter Out of Place and Democratic Hope.” In these times, when we hear a lot about national purity, racial purity, and sexual purity, this post helps flesh out why the idea of purity can be problematic and how it might be contributing to some of the current challenges we are facing in the U.S. and around the world.

This is less practical than many of the articles on Lotus & Phoenix, but for those that are open to a longer-form piece or curious about digging deeper into some of the issues our world is currently facing, I think the length and deep-dive details will be worth it. If you are looking for a light read, you might click over to some of my shorter essays like Don’t Make Fun of People You Want to Agree with You or Reflections on the Pace of Things.

True Love Waits and Father-Daughter Purity Balls

If you are wondering what this has to do with what is going in our world today, stay with me for a minute. First, we take a walk down memory lane to 1995:

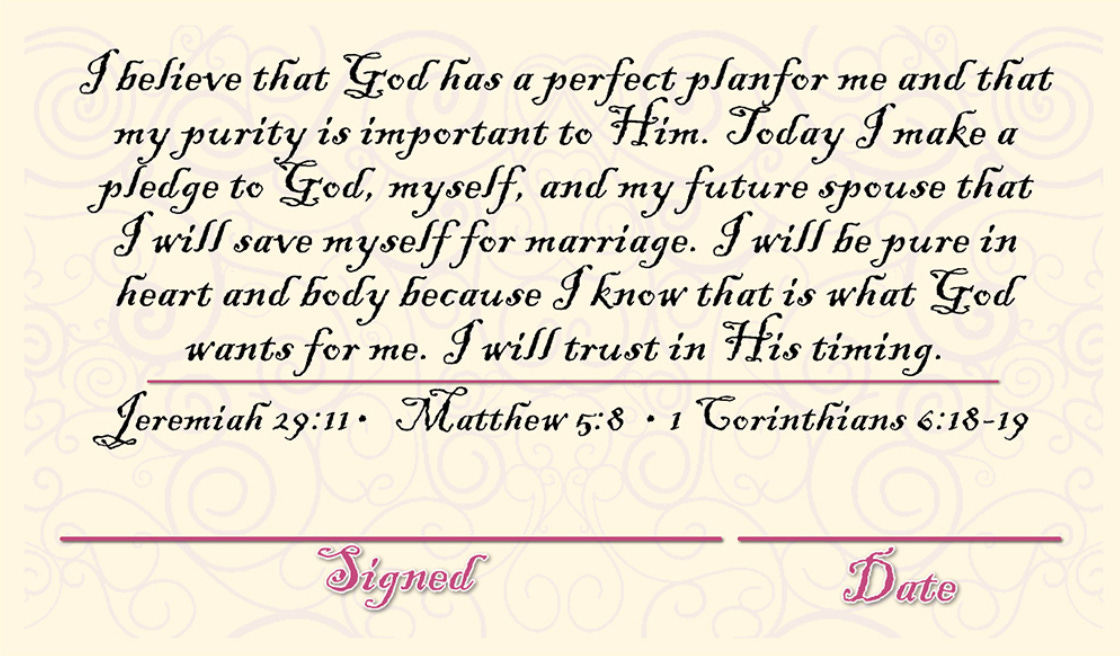

Like millions of teenagers across the country, when I was in high school, I signed a pledge to remain sexually pure until I was married. It came at the end of a youth group meeting at my large mainline church with an evangelical bent. There were presentations by straight, married adults about the joys of great married sex and a talk about how sex before marriage is traumatic for girls.

We learned about how God provides sex as a gift to married people. The focus was not on sin or doing something that was wrong because it was wrong. The emphasis was on the practical negative consequences of sexual activity before marriage and the rewards of a great sex life once you were in a marriage. The reason to stay “pure” before marriage was because, otherwise, bad things would happen to you (heartbreak, STDs, etc.). In this rendering, sin was God’s way of protecting you from bad things.

The event culminated in the distribution of business card-sized purity pledges that we were to sign and drop off as we left.

I mostly believed what I was taught about sexuality in church: God planned sex only for straight married people. You should not “do it” until then. If you did “do it” before you were married, you were guaranteed some serious problems. When I was in college, I sat, mouth agape, as an acquaintance told me that she had slept with three men whose last name she did not know. She said it casually, apparently equally shocked that I could think there was a serious problem with this. Did she feel sad, I asked? Empty? Alone? Abandoned? She assured me that she felt none of these things. She did not appear traumatized. She had never gotten pregnant, had an abortion, or even contracted sexually transmitted infection. How, I wondered, was this possible, in light of what I was taught?

In order to make sense of this, I took the next logical step: I went to graduate school and studied it for about ten years.

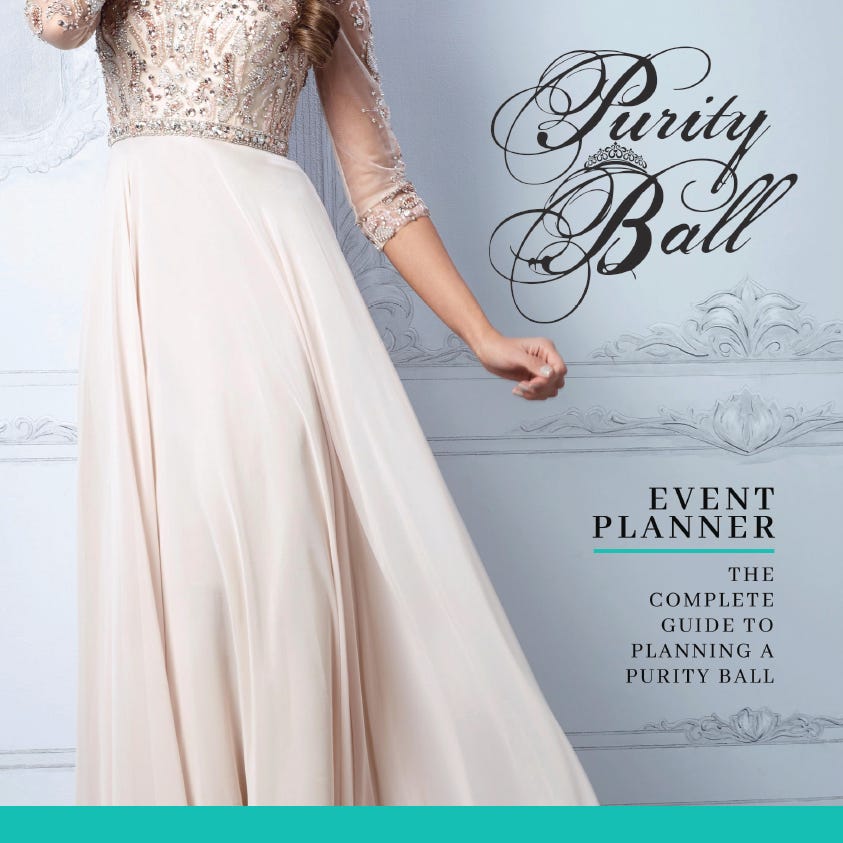

Fast-forward to 2002 and I am a grad student picking a topic for my master’s thesis. I had stumbled across reporting on “purity balls” which were an up-and-coming trend where dads and daughters got dressed up in prom-like clothes (or wedding-like clothes, depending on the tradition) and went to a fancy event where dads promise to protect their daughter’s sexual purity. The first father-daughter purity ball took place in 1998. Leslee Unruh, founder of The Abstinence Clearinghouse, claimed that approximately 1,400 purity balls took place in 2006 and that the number of yearly balls had grown to 4,700 by 2008. Exact numbers are impossible to state reliably, but there were a bunch of them. They are less common these days, but not totally gone.

I was both fascinated and horrified. These were sponsored by churches and attended by families that, by and large, loved their daughters and wanted good for them. Despite claims to the contrary, I don’t think most conservative Christians hate women or their daughters. I know this because I grew up with a lot of conservative Christians, but also I’ve now spent about twenty-five years studying evangelical Christianity in the U.S. I’ve visited countless churches and purity events, and interviewed hundreds of people who have been a part of this. I have never gotten the sense that purity events or teachings were, on the whole, nefarious. Sure, while you have your occasional creepy/weird/mean person (like in all walks of life),1 mostly, parents were like, “We want our daughter to know she is loved and her dad will protect her. We want her to know that she is valuable and special. And also it is fun to dress up and have a fun event with your dad. Also we don’t want her to get pregnant/get an STD or, or treated badly by some loser boy.”2 The daughters were excited to get dressed up.

That said, the pledge that was used at a lot of these purity balls was concerning to me:

I choose before God to cover my daughter as her authority and protection in the area of purity. I will be pure in my own life as a man, husband and father. I will be a man of integrity and accountability as I lead, guide and pray over my daughter and my family as the high priest in my home. This covering will be used by God to influence generations to come

Why was this just about girls? Where were the moms and sons in this? Why talk about purity and not abstinence? So many questions!

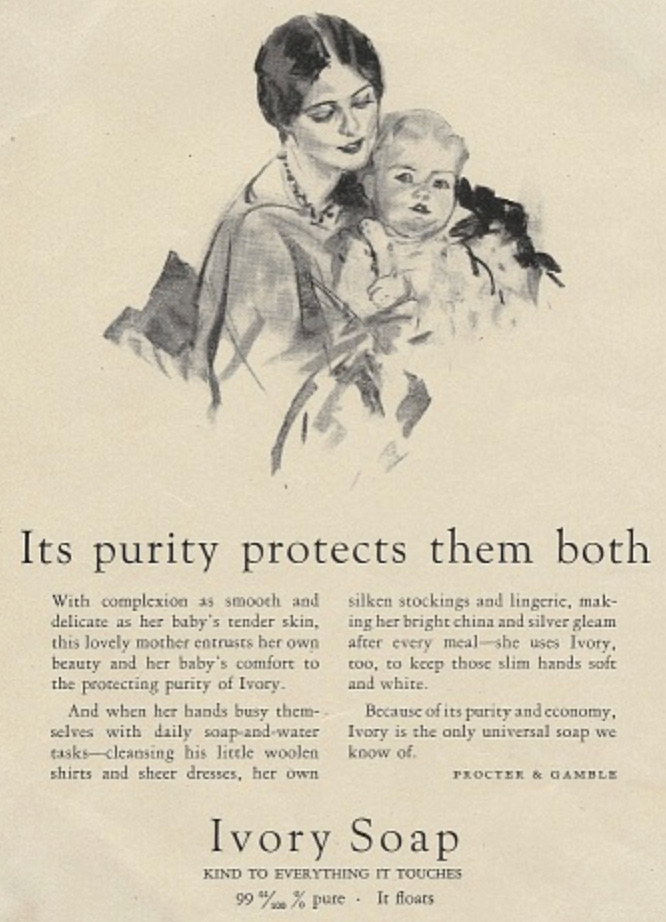

This led me down the rabbit hole of purity research, which led to bigger questions: Why is purity such a thing - in religion, with sex, with bodies? With nations and races? What does purity even mean? How do we know what counts as pure? And is this somehow related to my soap that is literally called Purity and my water where the name of the brand is Pure Life?

Purity as a Way of Trying to Keep Things in the Right Order

Although not immediately obvious, the idea of purity (of bodies, gender, water, soap, nations, etc.) depends on the idea that there is a proper way that things should be ordered. Again, stay with me. We’re getting closer to what this has to do with whatever is going on around us (*gestures broadly at all the things*).

Your water is branded as pure because the marketers want you to know (or believe?) that it doesn’t have things in it that shouldn’t be there. Your soap is called Purity because the creators of the soap want you to know (or believe) that there is nothing in the soap that should not be there (like toxic chemicals). Also, soap with pure in the name evokes a sense that the soap itself is pure, and also that it will help keep your skin/body free from things that shouldn’t be there (dirt, chemicals, and contaminants, etc).

What could be wrong with this? Shouldn’t we want pure water and pure soap and other pure things?

The short answer is, mostly, no. Your water and your soap are mostly not “pure” in the way that the marketers would like you to believe. The marketing of pure things plays off of long-standing patterns in human cultures that not only organize people and things (black/white, good/bad, rich/poor, man/woman, Jew/Christian, etc.), but also likes to rank these people/things that have been organized. Pure is generally perceived to be better than impure. Certain nations like to think they are better than other nations. Certain genders, races, clans, tribes, subcultures, and classes like to think they are better than others. In order to be better, and thus have more power, people need to be categorized and ranked, and those categories need to be enforced.

Remember how the Nazis wanted (want?) a “pure” race/nation where people “who didn’t belong” were systematically murdered? Remember the so-called “one-drop rule” in the U.S. that justified murder, enslavement, and discrimination against Black people because they had African ancestry - that is, because they did not have “pure blood?”

So, like nations or groups that some people wish to make “pure,” bodies are perceived to be pure when they don’t have things either in them or on them that “shouldn’t be there.” For instance, in the beloved Netflix series Bridgerton, we see that a married woman who has had her husband’s penis in her vagina is considered to be pure. That is, she had a thing in her that “belonged there.” But an unmarried woman who has had a penis inside her is considered impure and at risk of being shunned and un-marry-able. That is, her body had something in it that was perceived not to “belong” there.

This all relates to things being where they should or shouldn’t be, and who gets to decide this. By this logic, a penis should not be in the vagina of unmarried woman. Likewise, according to this purity framework, the penis of husband should be in the vagina of married woman. This is not decided, of course, primarily by individual people or couples, but rather by a bigger system made up of families, church, society, culture, etc.

This is not only in the imaginary land of Bridgerton, of course, but I’m trying to use a pop-culture example to highlight the point here. (As I like to tell my kids, “I am hip. See?”)

We can thank anthropologist Mary Douglas for helping us to understand this better in her book Purity and Danger back in 1966, where she makes the case that “dirt” (anything which causes impurity) is “matter out of place.” In short, something becomes “impure” because things are not where they are supposed to be - something is out of place. Douglas notes:

[Dirt] implies two conditions: a set of ordered relations and contravention of that order. Dirt, then, is never a unique isolated event. Where there is dirt there is a system. Dirt is the by-product of systematic ordering and classification of matter, insofar as order involves rejecting inappropriate elements.

Thus, we can see that the father-daughter purity balls make sense as a ritual to strengthen and affirm the correct ordering of the world. Fathers are understood to be the head of the household and the protector. Daughters are understood to be weaker, vulnerable, and need protecting.

Purity balls, along with the purity pledge-card signing ritual millions of 1990s kids went through, were an effort to keep things in the right order. The concept of sexual purity functions (mostly unconsciously) to maintain a proper ordering and classification with respect to the family, the church, God, gender roles, and bodies.

It was not that those putting on purity balls or encouraging people to sign purity pledges were all like, “Ah-ha, this is a great ritual to maintain the hierarchical systems of power that benefit us, keep the world in the right order, and help us to feel secure in an insecure world.” But, in many ways, this is what was going on.

Likewise, we can think of the efforts of the Nazi party in the 1940s to promote racial and national purity as an effort to maintain the “right” order and hierarchy of things. Certain people were understood to be good, valuable, and worthy of power. Others were not. The Holocaust, where 11 million Jewish, gay, disabled, and other people considered to be “contaminating” the German nation and “Aryan” race were systematically kidnapped, tortured, and murdered in an effort to “purify” the German nation and “Aryan” race, was an attempt at keeping people “where they belonged” and maintaining a certain order. The violent efforts at “purification” were part of what Mary Douglas called “systematic ordering and classification, insofar as order involves rejecting inappropriate elements.”

Okay, but can we just not murder people but still have pure soap and water?

As people face insecurity, they often wish to order things “correctly,” often to maintain structures and systems from which they benefit. Sometimes this is conscious. A lot of times it is not.

The construction and promotion of various forms of purity provides a way to argue both that 1) there is a proper order to things and 2) also that “things” are not currently in their proper place within this order. Purity frameworks often represent fantasies that we can somehow be saved from the chaos and insecurity of the human condition. We insist on a proper or natural order of things, even though it takes an incredible amount of resources, violence, and coercion to maintain or attempt to return to this order.

So the mental structures inside us that make us think that pure soap is good and that we need to take a shower every single day despite the ways that this can actually decrease our health are the same mental structures that lead to people wanting neighbors who look like us and speak the same language as us, and are the same things that contribute to the idea that it is good to make sure girls don’t have sex before they are in a heterosexual marriage.

One of the uses of research on purity is that it can help us see the ways these systems are functioning. This is mostly useful not because we then get to say, “Aha- look at those bad people over there creating the wrong systems unlike us who want good systems,” but instead to ask, “Hmm, I see that these systems are functioning and working to create a certain kind of world. Is this the kind of world I want? What might I and my community be able to do to adjust this now that we see this and how this functions in our society?”

So what does this have to do with the moment we are in now?

If you are one of my most dedicated readers that has gotten this far, you might be wondering, “Okay, so we can agree that sexual purity teachings are not good3 and also Nazi teachings about pure nations and races are also problematic. But what does this mean for me today, someone who is not promoting sexual purity and also not a Nazi?”

That is a good question! I want to turn to a quote from the brilliant Alexis Shotwell whose book Against Purity is one of my favorite books. She writes,

There is no food we can eat, clothing we can buy, or energy we can use without deepening our ties to complex webs of suffering. So what happens if we start from there? (p. 5)

This is helpful because I think it helps us remember that we are not going to figure out the perfect way forward. We are woven into a really messy world where we cannot disentangle ourselves fully from systems which are harmful. To be righteous - that we as individuals or we as [insert relevant group] are really getting things right or that we really and uniquely know the right way to be, speak, behave, etc. is to, again, perpetuate another purity fantasy of good/bad, right/wrong, sinful/holy, clean/dirty, etc.

What we can do, however, is to pay attention to the ways we see these purity frameworks playing out in front of us - in our homes, in our religious communities, in the news, in our neighborhoods, and on the national and global scale. As we observe these happening, we can ask things like, “What story is that telling about how the world should be ordered?” or “Is that story about [racial, sexual, national, bodily, religious, etc.] purity ranking groups of people as more or less worthy of safety, love, care, health, or freedom?”

My (small) readership of this newsletter is diverse. I know that I am speaking to a crowd of people that are politically and religiously diverse. I hope that by going through some of the functions of purity, we might take a look at the ways that notions of purity shape how we understand ourselves and others in these hard times, and how this might be influencing how we act and build our little worlds.

For instance, across different parts of our political and religious spectrums there is a sense that there is an ultimate truth that we can have access to and we show little grace, understanding, or flexibility when someone deviates from what we consider to be the right perspective. This has contributed to what is called cancel culture, as well as bullying, ruined family dinners, broken friendships, and more sorting of our life to include only the people that we consider to be correct. At its heart, this comes from notions of religious and ideological purity. You are either in or out, you are either good or bad, you are either the part of the problem, or part of the solution.

The reality of life lived together in a complex world with other people is often messier than this. Most of us contribute to making things worse, in one way or another. Many people contribute to making this better, in one way or another.

When we insist that our friend groups, our political movements, our religious communities, or our neighborhoods are only appropriate for a certain kind of people - we (often unintentionally) promote certain forms of purity that move forward a “systematic ordering and classification of matter, insofar as order involves rejecting inappropriate elements.”

I hear the protests already. You want me to invite my racist uncle over for dinner? You want my friend group to welcome someone who voted for [fill in the blank of the person you think is horrible]? You want me to hang out with people who disparage my [fill in the blank with identity that you feel is being disparaged]?!?

Take a deep breath. This is not a decree that insists I know what is best and that you must invite your local White Supremacist or Communist over for dinner to hear about her grievances and give her cookies.

The underlying point is to invite us to see the places in our own lives where we might be drawing on or acting on notions of purity that have the potential to be problematic and might contribute to creating a world that is not the kind of world we want to live in. My point is that purity often shapes how we understand the world and how we act in the world even if we are not pushing sexual purity pledges on our kids or joining the local neo-Nazi march.

It is easy to look out in the world and see all the bad things that other people are doing. It is also easy to project our lament, anger, and fear onto other people who seem to be doing worse things than we are doing as we just try to keep our lives together.

I often tell my psychotherapy clients, when we identify a pattern or issue that is causing them pain or problems: “Hey, don’t fret about this right now and imagine you have to somehow change this THIS WEEK. It is a lot to be able to recognize the patterns in our behavior that were shaping how we act and live, but we didn’t really see or understand. Most people go through life never having the time or space to really see what is going on and what is driving our behavior. So for now, we can just appreciate that we are seeing the pattern. There will be the space and the time to notice this, with some compassion for yourself about why you might have developed this pattern that you are thinking no longer serves you. Over time, we can figure out how to make shifts and tweaks, but for now, just being able to see this pattern and having this insight is great.”

And I would say that this is my offering as we consider the ways that purity frameworks might shape our lives - with our families, in our faith, in our politics, and in our communities. Let us pay attention. If we are able to do that, we might feel called to ask what shifts we can make. We might feel called to see ways we can shift the purity frameworks that sort and rank the world and people around us. May we be gentle with ourselves as we try to live and love in this world on fire.

This article includes excerpts from the following articles: “When Purity Cannot Save Us: On Matter out of Place and Democratic Hope,” Journal of Theology and Sexuality, April 2024; “Are You a ‘Trashable’ Styrofoam Cup?”: Harm and Damage Rhetoric in the Contemporary American Sexual Purity Movement, Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, 2018, “Producing High Priests and Princesses: The Father-Daughter Relationship in the Christian Sexual Purity Movement,” Religions, 2016. For more reading on issues of purity, you can also see Alexis Shotwell, Sara Moslener, Kathryn House, and Victoria Houser. For more on the way that our unconscious shapes our politics and religious lives, you can see Noelle McAfee and David McIvor.

December 7, 2025. Vol. 2, Issue 11.

A note on this space

This Substack started out as the newsletter for my psychotherapy practice, Lotus & Phoenix. I have come to realize that it needs to be slightly different than that. While I am a psychotherapist, I am also a researcher, non-profit leader, pastor, and parent. This space brings together my work in all of these areas.

I am experimenting with what this Substack will look like. For now, you can expect that this will be a place for original essays, reflections, and sharing of resources as we all try to love and live in a world on fire. Thank you for being here.

The fine print

Please note that this is for informational purposes only. Nothing on here is intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician, psychotherapist, or other qualified provider with any questions you may have about a medical or mental health condition. The use of the information provided on this site is at your own risk.

My research shows that this is a little different at the level of national leadership. I’m not going to go into the details in this post, but here I am talking mostly about the local level.

I don’t mean to minimize the harm and/or trauma and/or general unpleasantness that many who experienced these purity balls have endured. There is, in fact, an entire movement of people trying to recover from the various forms of harm caused by purity culture and I eagerly await Sara Moslener’s upcoming book After Purity which digs more deeply into this. But I think it important for those who are not part of evangelicalism or conservative Christian communities to realize that sexual purity teachings and events have been, in large part, carried out by average people trying to figure out faith, religion, family, gender, sex, and bodies, and are not some sort of grand conspiracy of bad actors trying to be abusive or awful. The reality is that many harmful things are not planned as such and it is often their banality and everyday-ness that gives them such power.

It is important to note that sexual abstinence or sex only in a committed relationship or marriage are perfectly reasonable decisions for communities or individuals to practice or adhere to. This post is not addressing this issue, but specifically addressing teachings related to sexual purity.